Methods

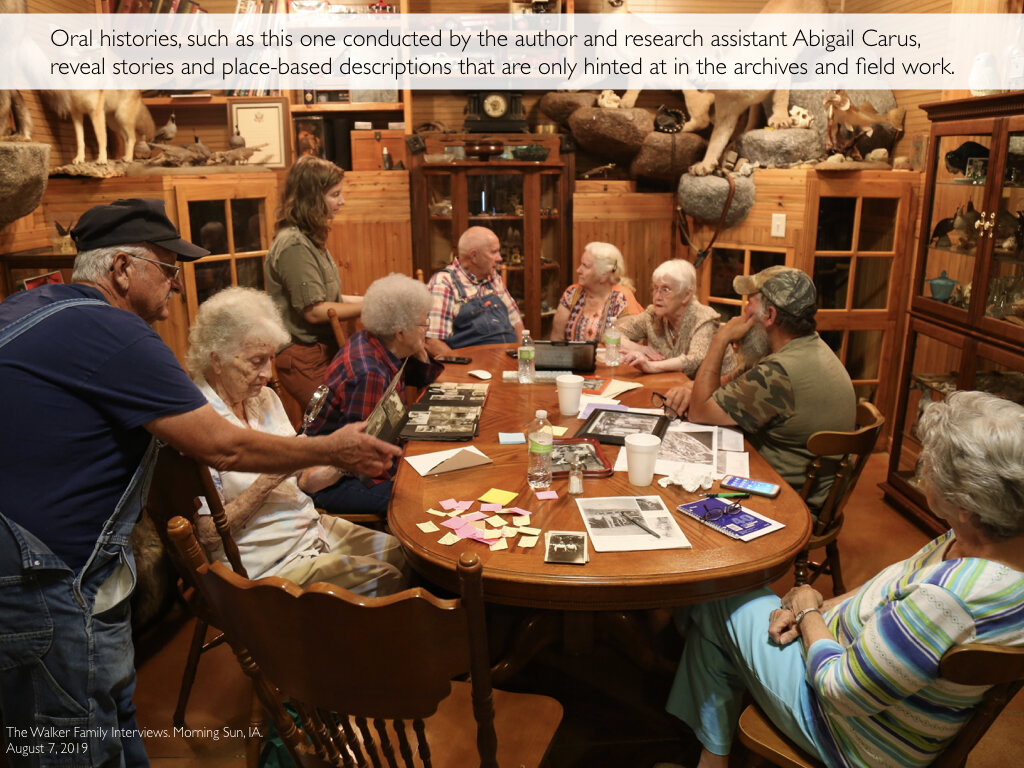

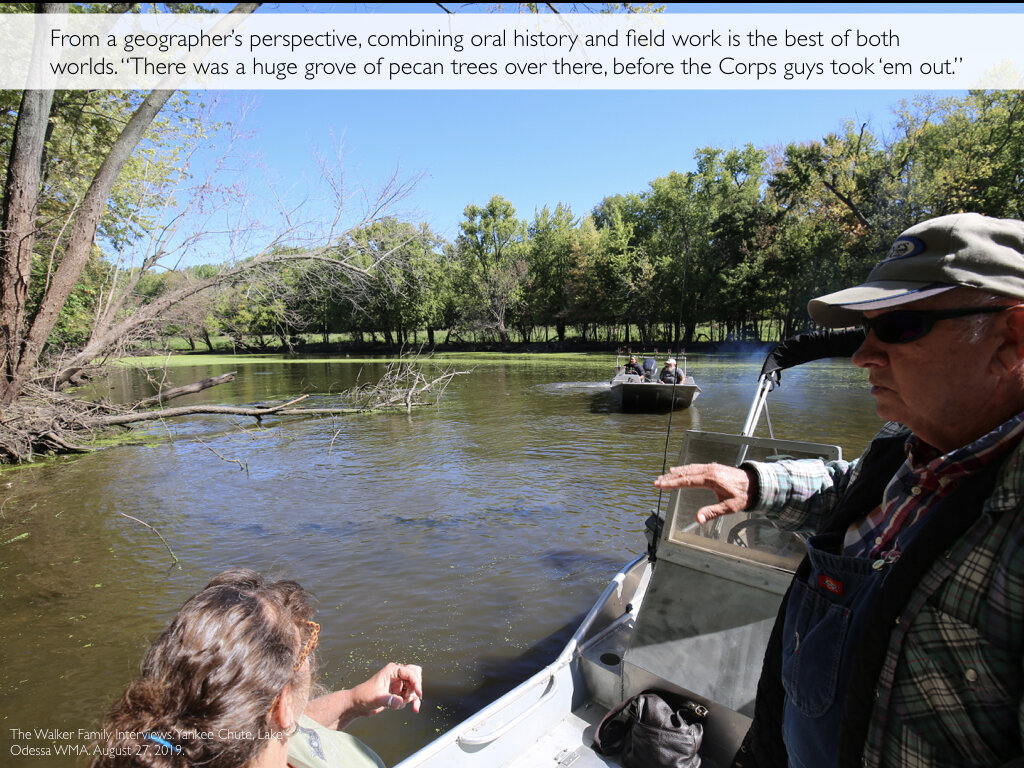

Two Mississippi uses a series of interdisciplinary methods to explore change on the Upper Mississippi since the 9-foot project, including “micro level” repeat photography, Geographic Information Systems mapping, archival research, and oral history.

Micro Level Repeat Photography

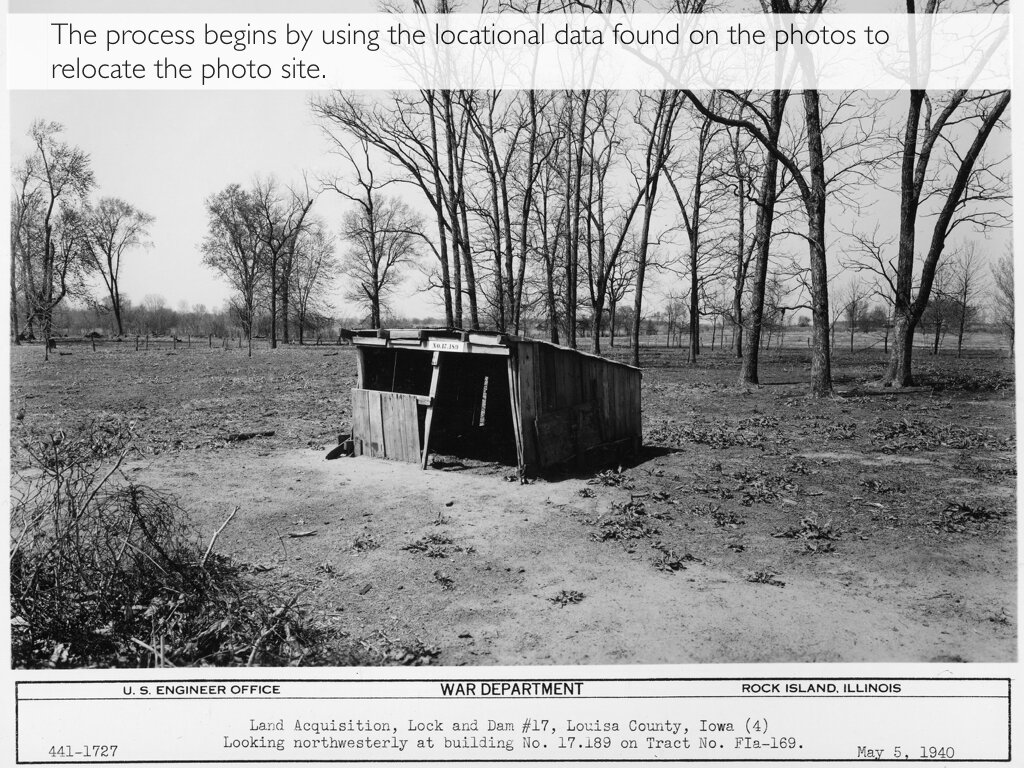

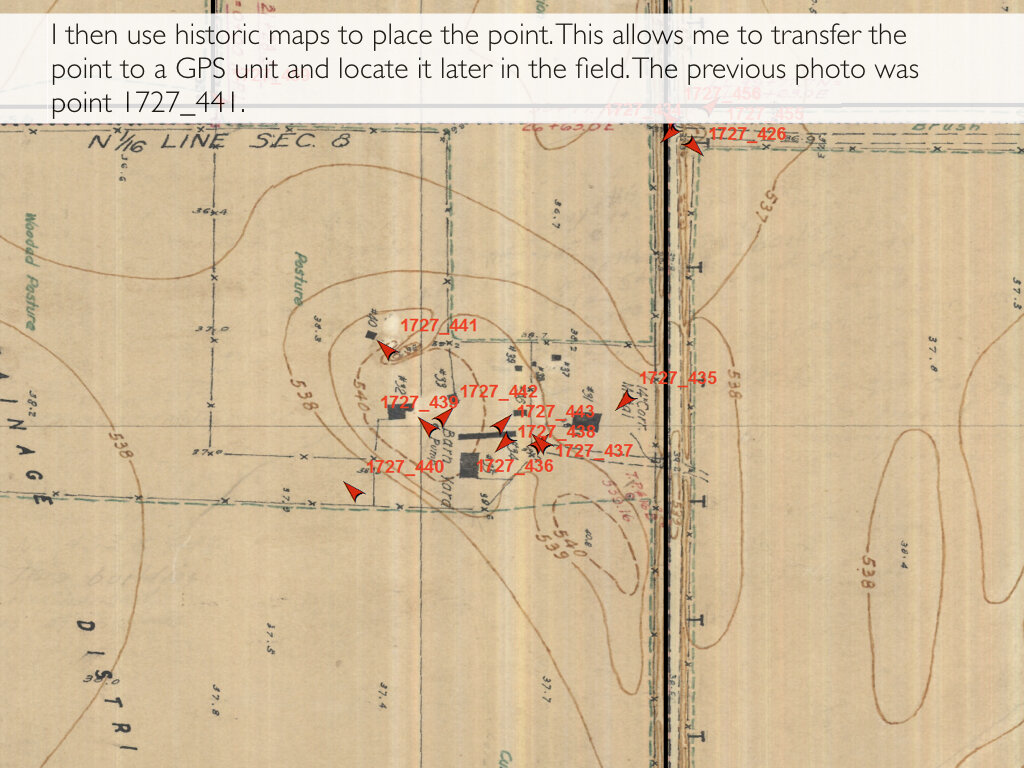

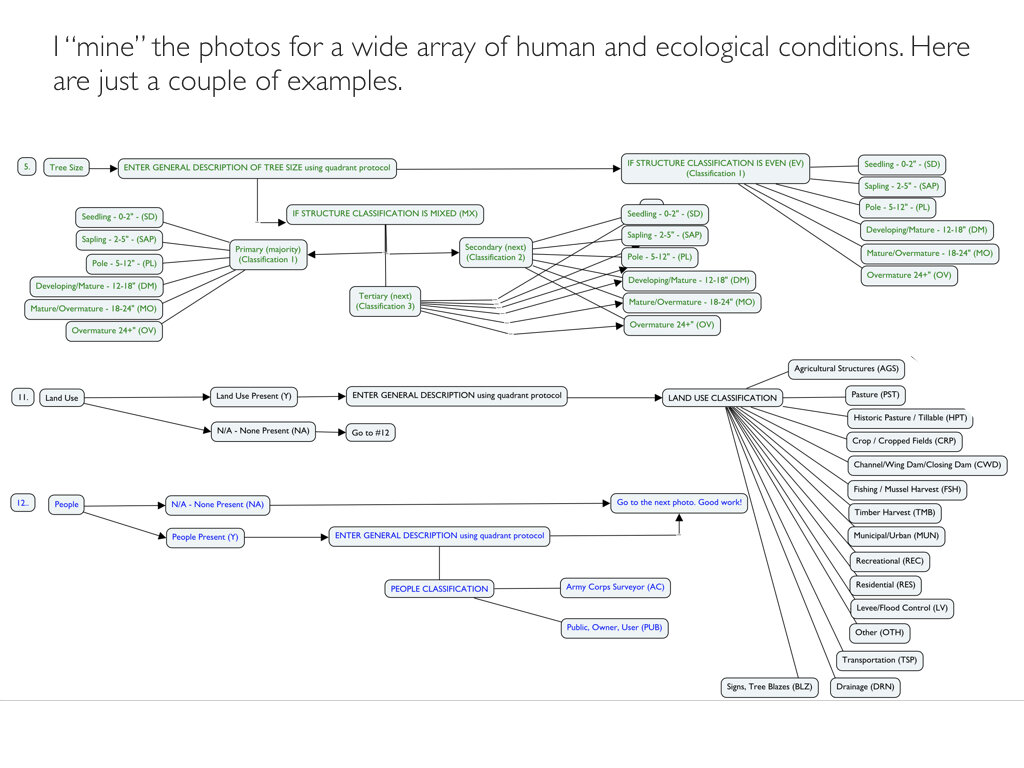

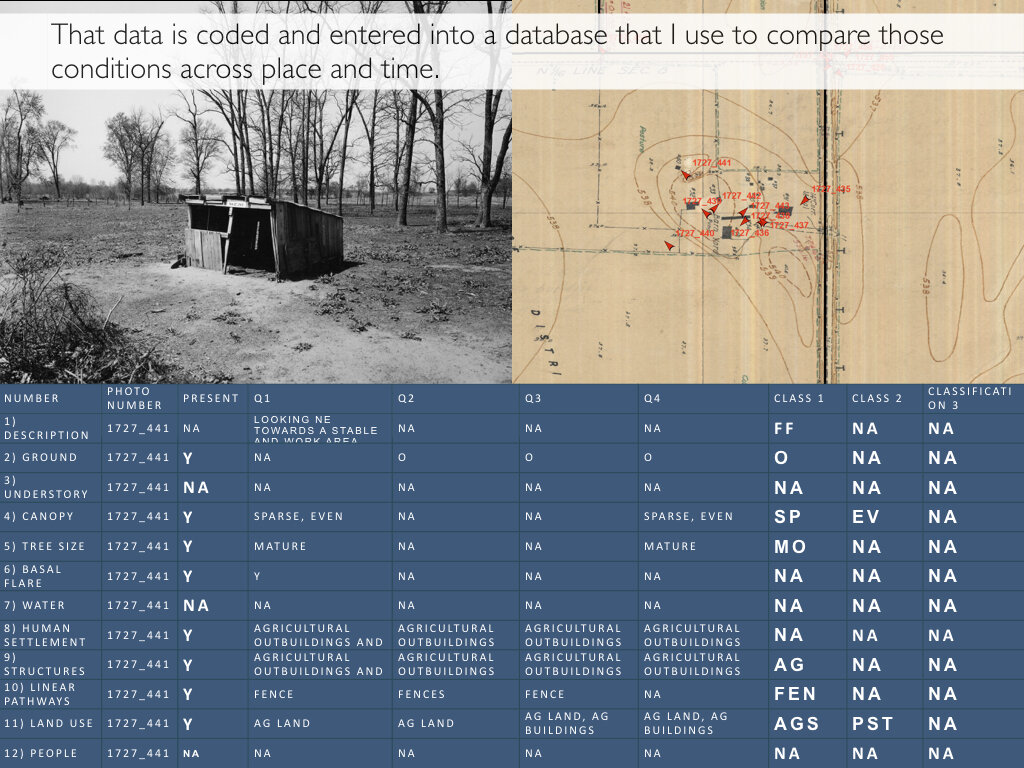

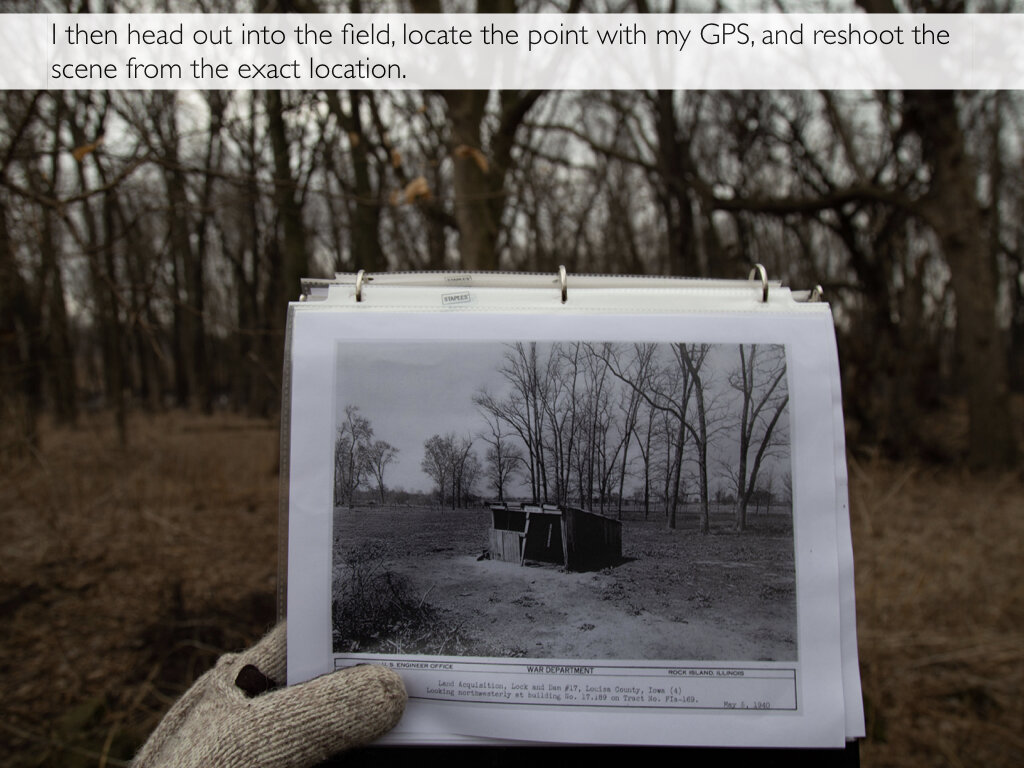

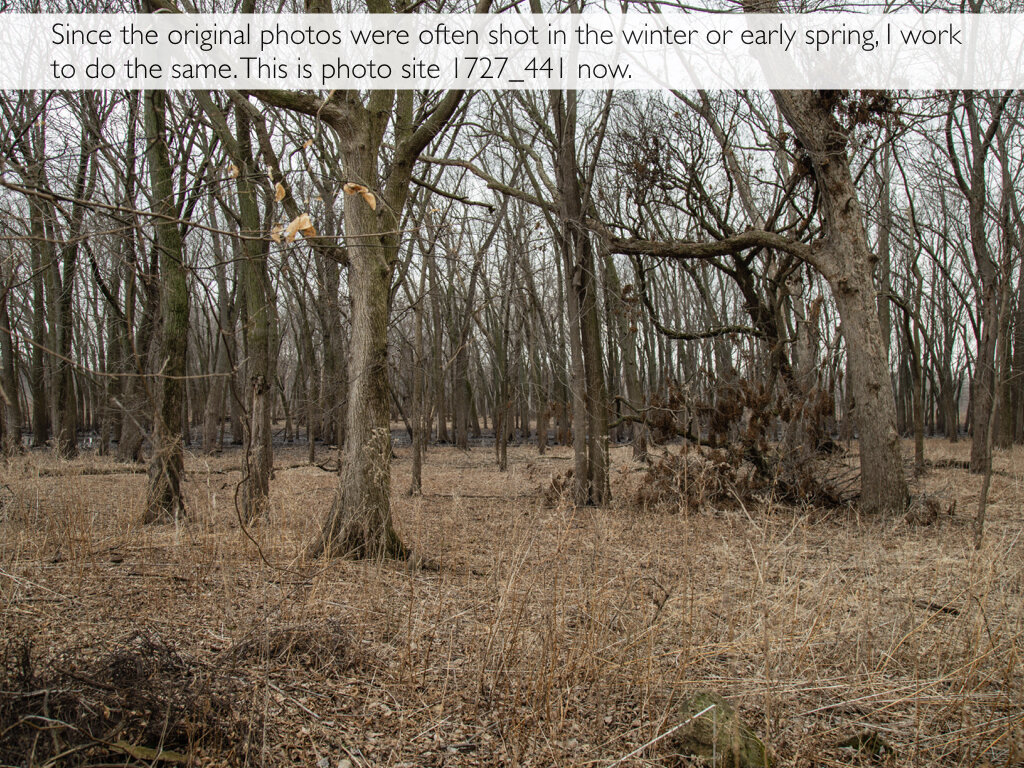

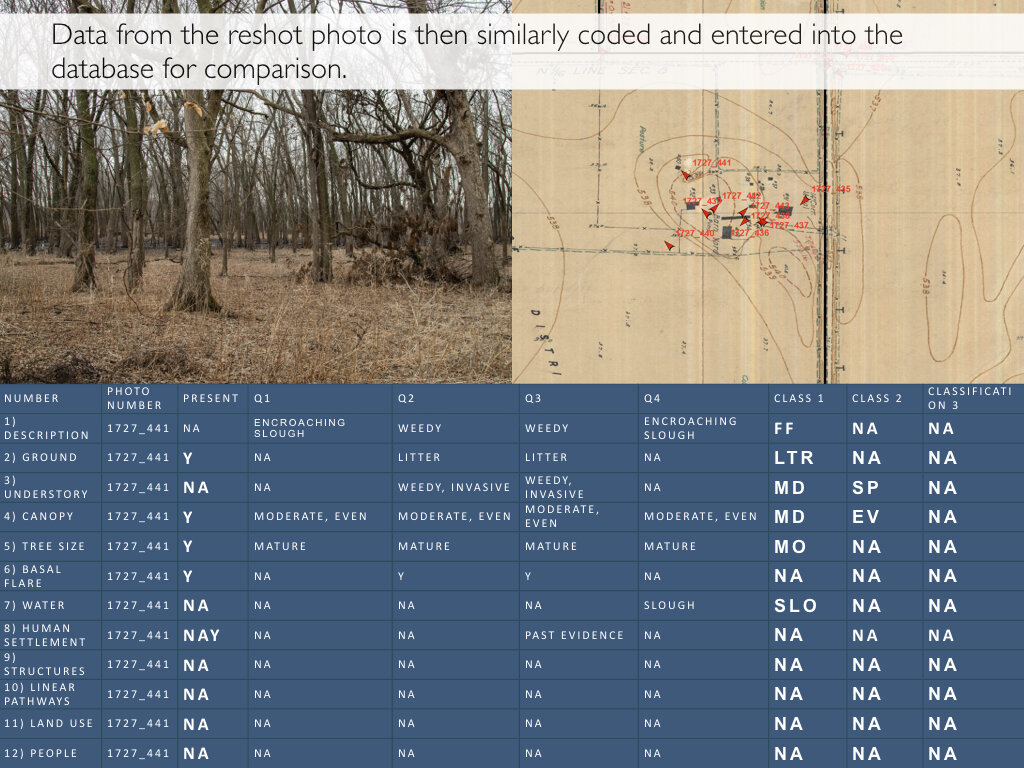

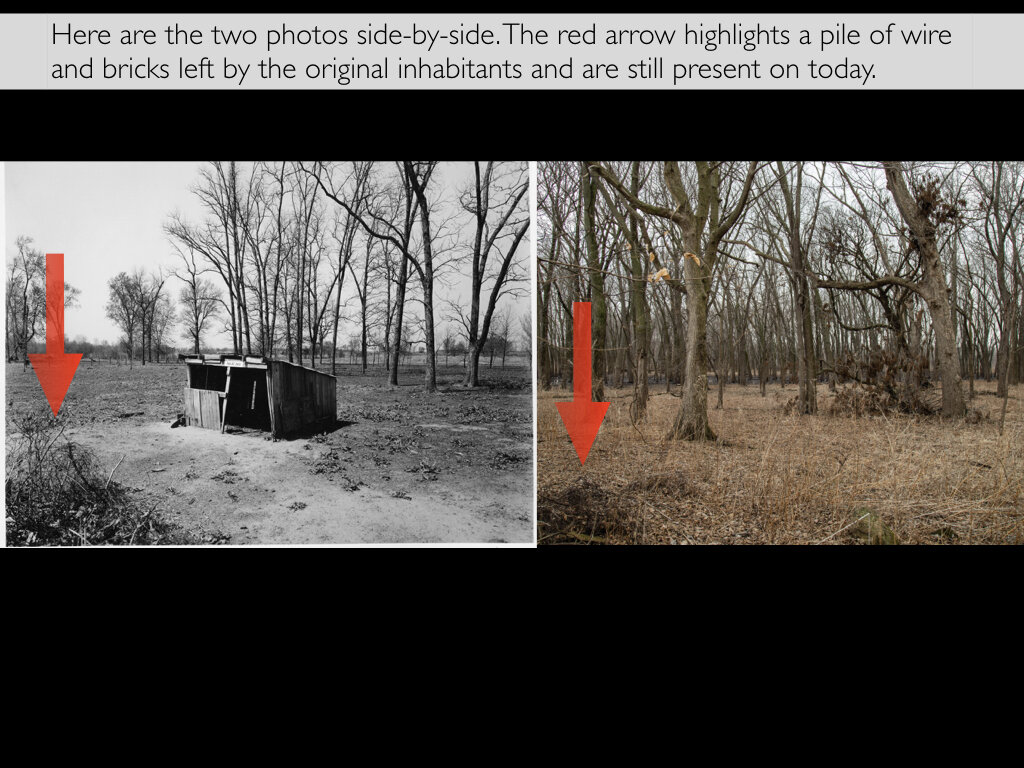

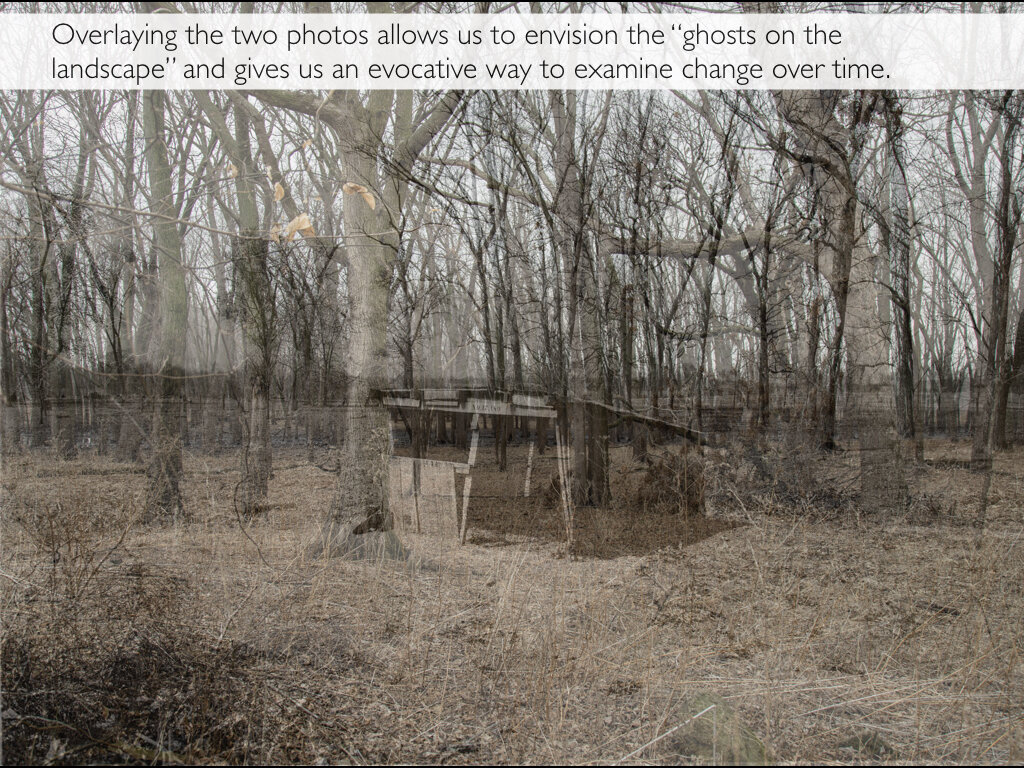

Traditional repeat photography often uses grand landscapes to explore change in a place over time. Two Mississippi utilizes a process I’ve named “micro level” repeat photography to explore human and ecological change on the Upper Mississippi over the past 80 years. I use data from thousands of photos originally shot by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1936 and 1940 to tell this story. These photos are condensed within a relatively short distance in Upper Mississippi pools 16, 17, and 18. I “mine” each original photo for a dozen social and ecological conditions - including soil and ground cover, tree size and structure, inundation, and human land use. I then “reoccupy” the site and photograph the same scene - nearly 80 years after the original. These photos are similarly “mined” for data. When compared, patterns of landscape change emerge that we can use to assess social and ecological trends. This process allows me to understand the larger social and ecological change on the Upper Mississippi.

Geographic Information Systems Mapping

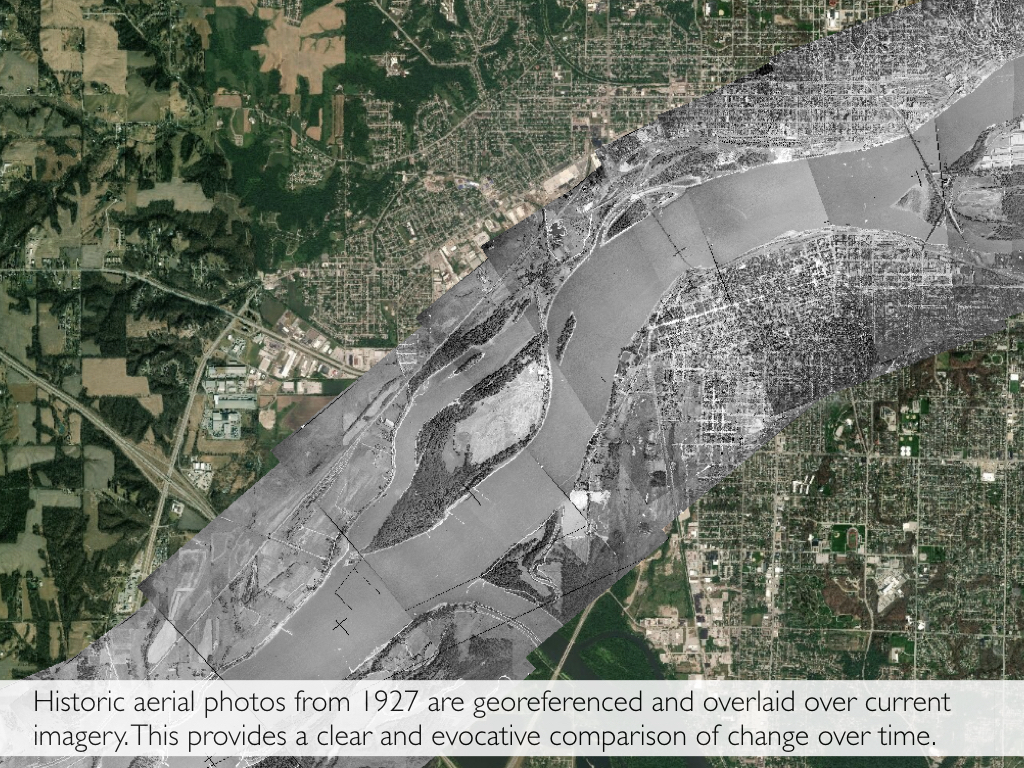

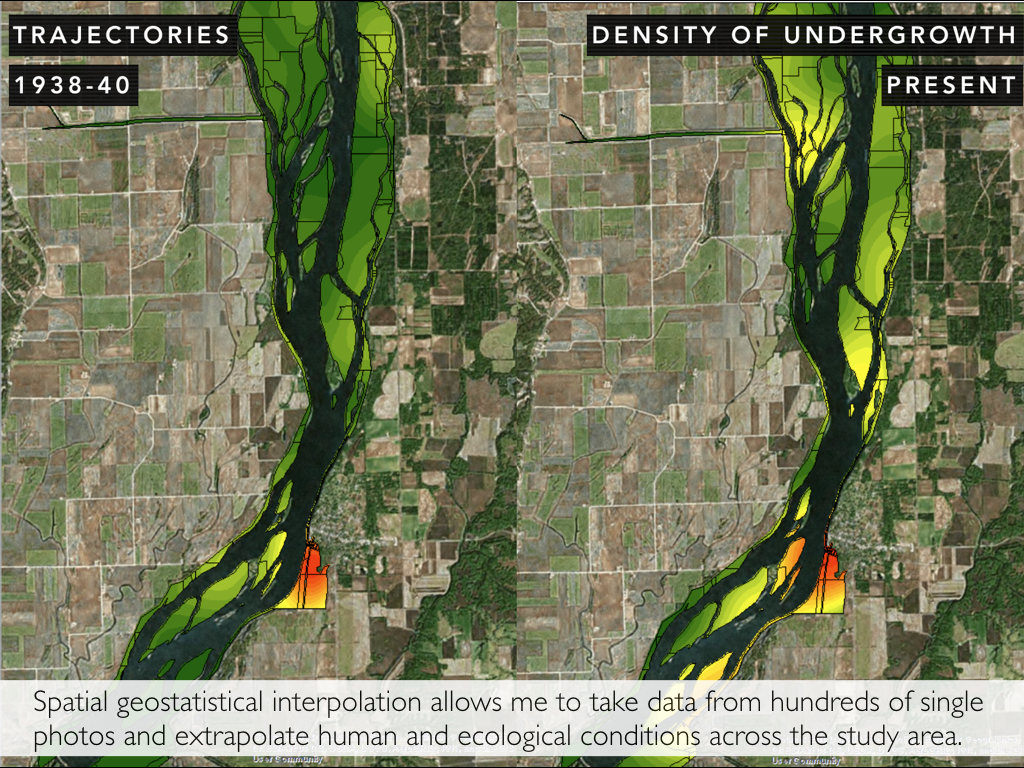

Historic and current human and ecological patterns are mapped using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). The data mined from these photos are single points of data that, when analyzed across the entire landscape, can be used to describe spatially continuous phenomena. We use spatial geostatistical interpolation to “fill in the gaps” and predict a surface that estimates the values of our data at other locations in the study area. This allows us to represent the past and present human and ecological landscapes with some statistical certainty. We can then use this data to assess trajectories that may be important for land resource managers. Historic aerial photos from 1927 are also georeferenced - or correctly overlaid in space - with current imagery using GIS to create a visual record of change.

Archival Research

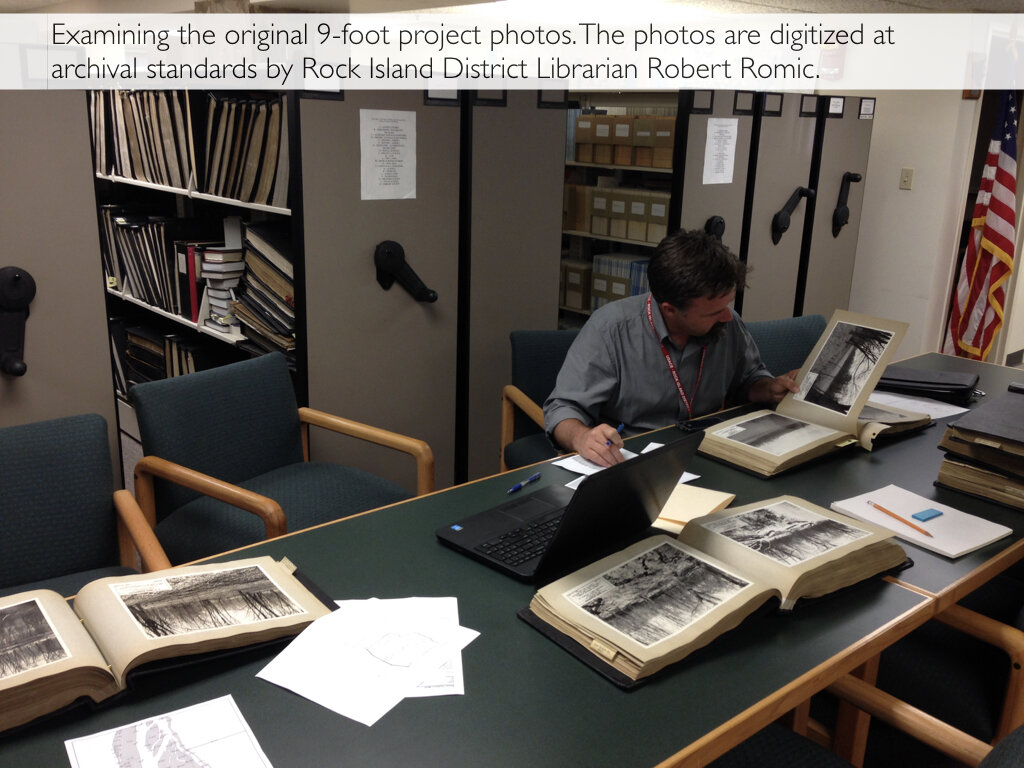

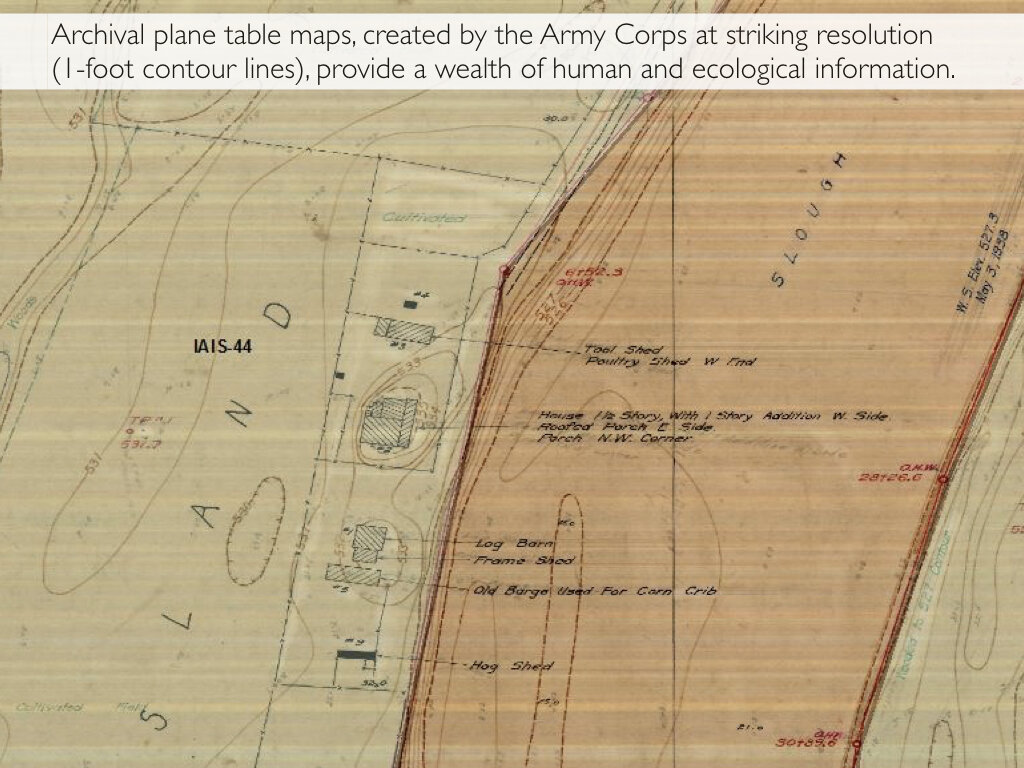

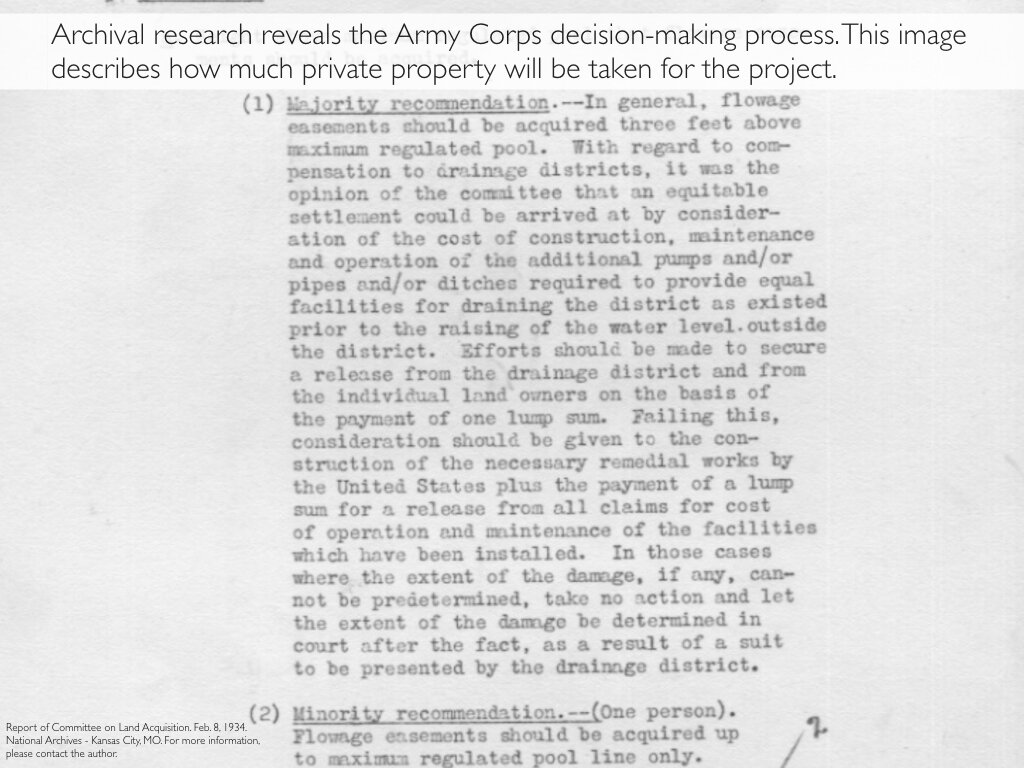

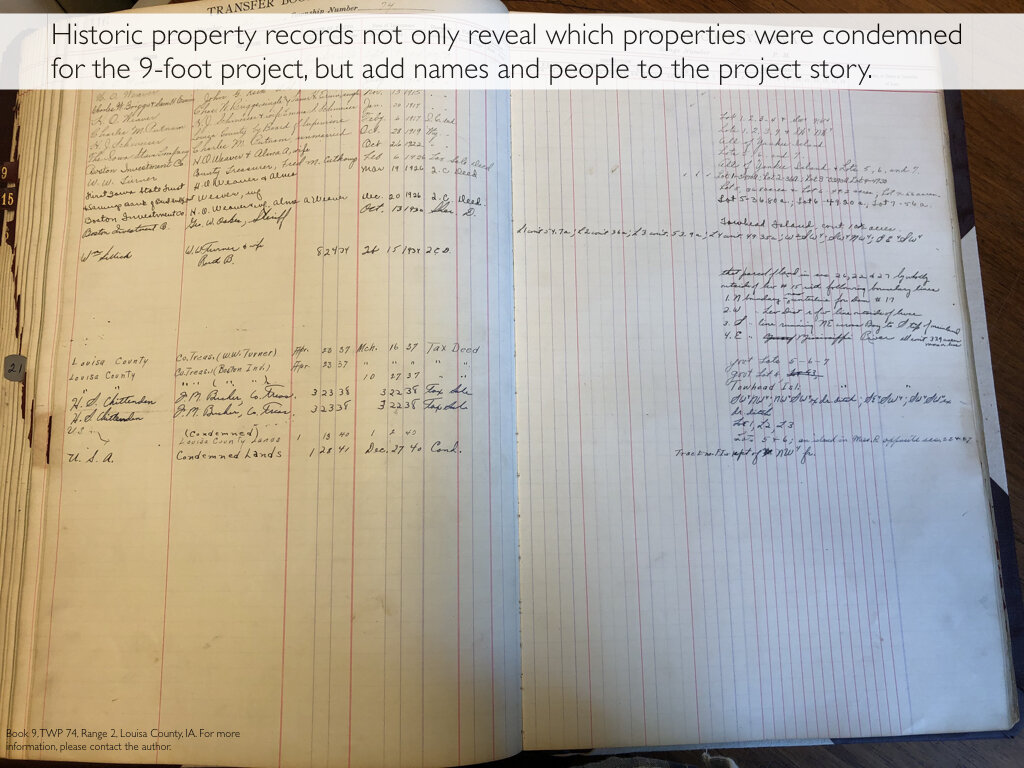

The roots of this project are found in the archives. Archival research contributes to Two Mississippi in three ways. First, archival research allows me to tell a historical geographic landscape story of change over time. Two Mississippi began at the Technical Library, Rock Island District of the Army Corps of Engineers. In the months leading up to the 9-foot project, the Army Corps painstakingly photographed, mapped, and documented thousands of landscapes impacted by the 9-foot project. This remarkable archive consists of thousands of photos taken on the eve (sometimes literally) of the Upper Mississippi River’s largest manmade alteration. This archive establishes a visual benchmark of the cultural and ecological landscapes that existed in the Upper Mississippi before its single greatest manmade transformation. Second, archival research conducted in the National Archives and Records Administration Regional Offices in Chicago, IL and Kansas City, MO has allowed me to assemble the agency story; Army Corps memorandum, directives, and notes reveal the internal discussion the agency held as it implemented the 9-foot project. Finally, archival research has also been used to intertwine the landscape and administrative stories with a more human one. I have accessed property and land use records from a variety of county courthouses across the Upper Mississippi which enables Two Mississippi to put a human face and voice to the 9-foot project.