A View from the Ditch: Photo set 1780. Pool 17. Copperas Creek, IL.

Early in the 1930s, Army Corps engineers recognized a significant financial and potentially legal threat to the 9-foot project. For decades up and down the Upper Mississippi floodplain cooperative drainage districts raised levees against spring floods and taxed their users to build drainage and pumping infrastructure. They operated collaboratively with the Army Corps and often relied on Corps expertise and financial largesse to mitigate flood damage - in some ways, federal conservation has its roots in moving water. But as plans for the 9-foot project progressed, the Corps had to face the fact that higher water could breach hundreds of drainage district levees. And that would be a disaster.

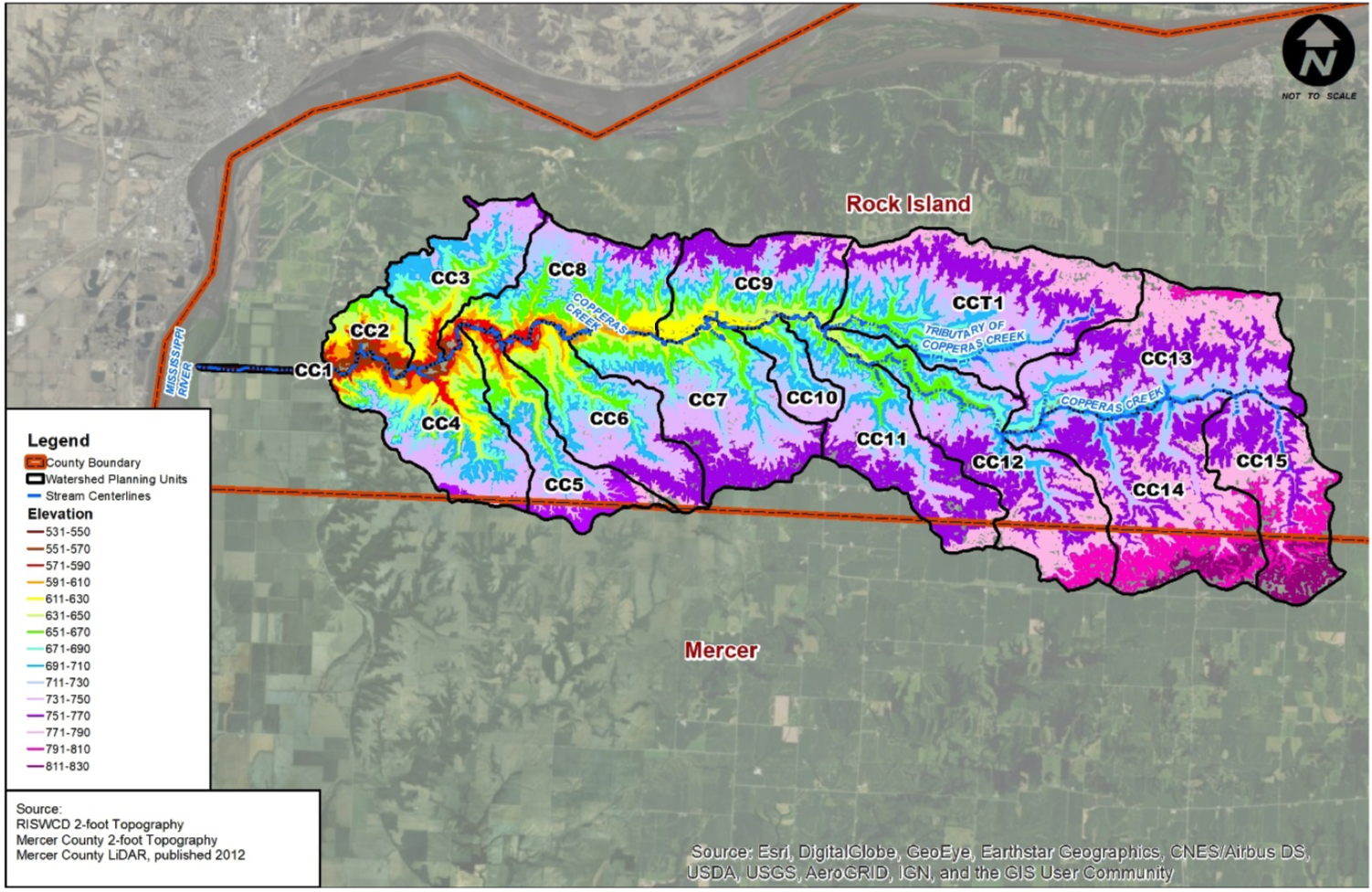

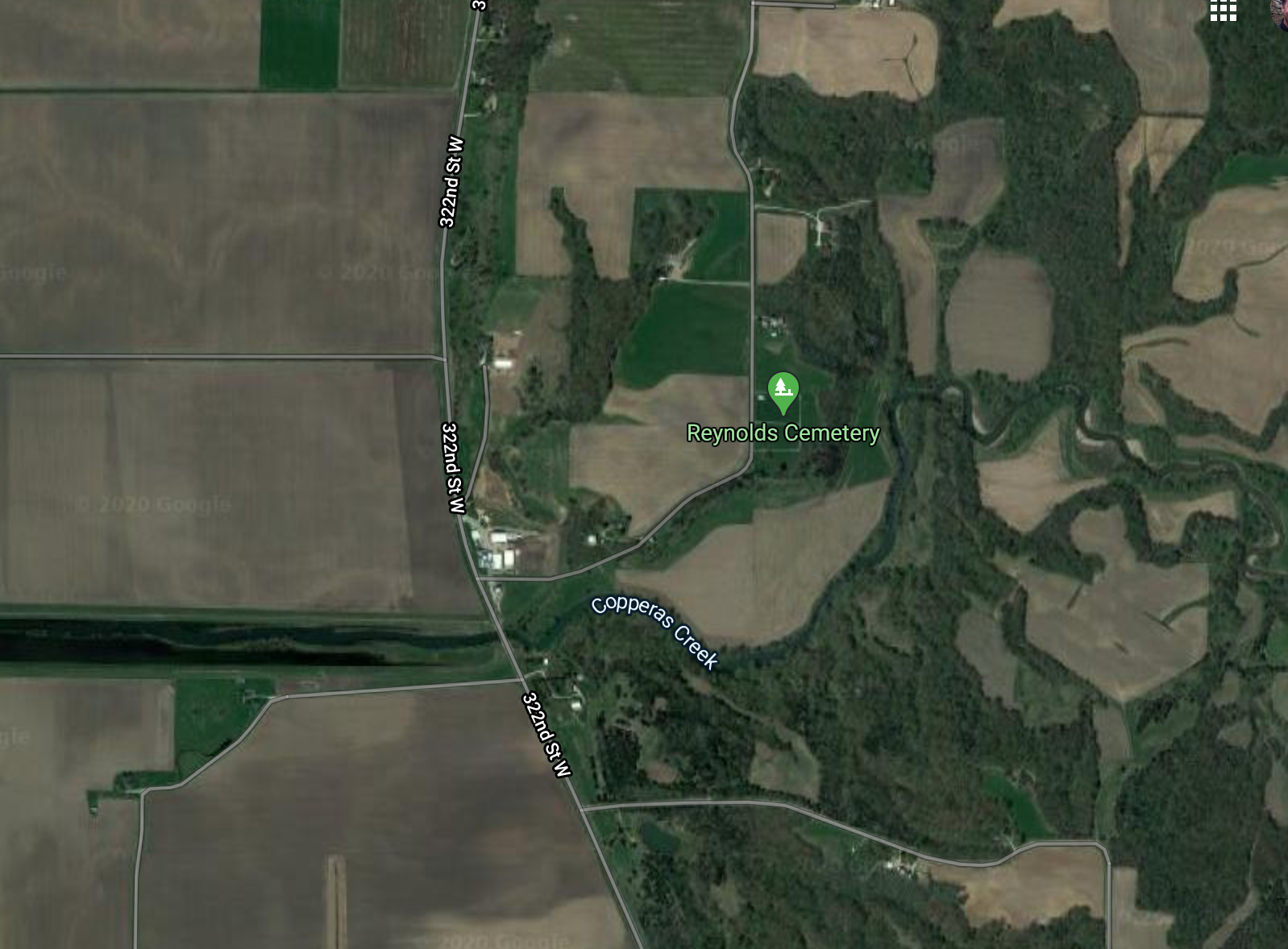

Copperas Creek is a 27-mile long waterbody that carves its way through the Rock Island County “highlands” until its confluence with the Mississippi River. Copperas Creek’s elevation drops approximately 200 feet along its run to the floodplain. Then Copperas Creek meandered. It filled backwater wetlands. It distributed rich, eroded sediment across the fertile flatland. It flooded, and then receded.

Anglo settlement along Copperas Creek began in the 1830s. Settlers farmed the floodplain without drainage or flood management until 1905 when, “the mouth of Copperas Creek … filled up (with sediment), and the backwater during heavy rains flooded the adjacent land” (63d US Congress, 2d Session, Vol. 22. 1914. p. 44). In December 1905, farmers along the creek formed the Drainage Union District No. 1 (south of Copperas Creek) and the Drury Drainage District (north of Copperas Creek). Copperas Creek was straightened from the point where the creek emerged from the hills to its outlet in the Mississippi near Blanchard Island. The channelized creek - now a ditch - had a 40 foot base. The Corps and Districts kept the channel in line with levees and routine sediment dredging. They constructed levees along the Mississippi above the Copperas Creek floodline and three feet above the high water mark of 1892 - the flood year on which the Corps of Engineers standardized all of their plans.

Plane Table Map of Copperas Creek channelization. If you look closely you can see past meander scars left in the topography before the Army Corps and the drainage district channelized Copperas.